What They Said, What They Didn’t

Behind the Tokyo summit’s polite phrases: distrust, deflection, and deadlock.

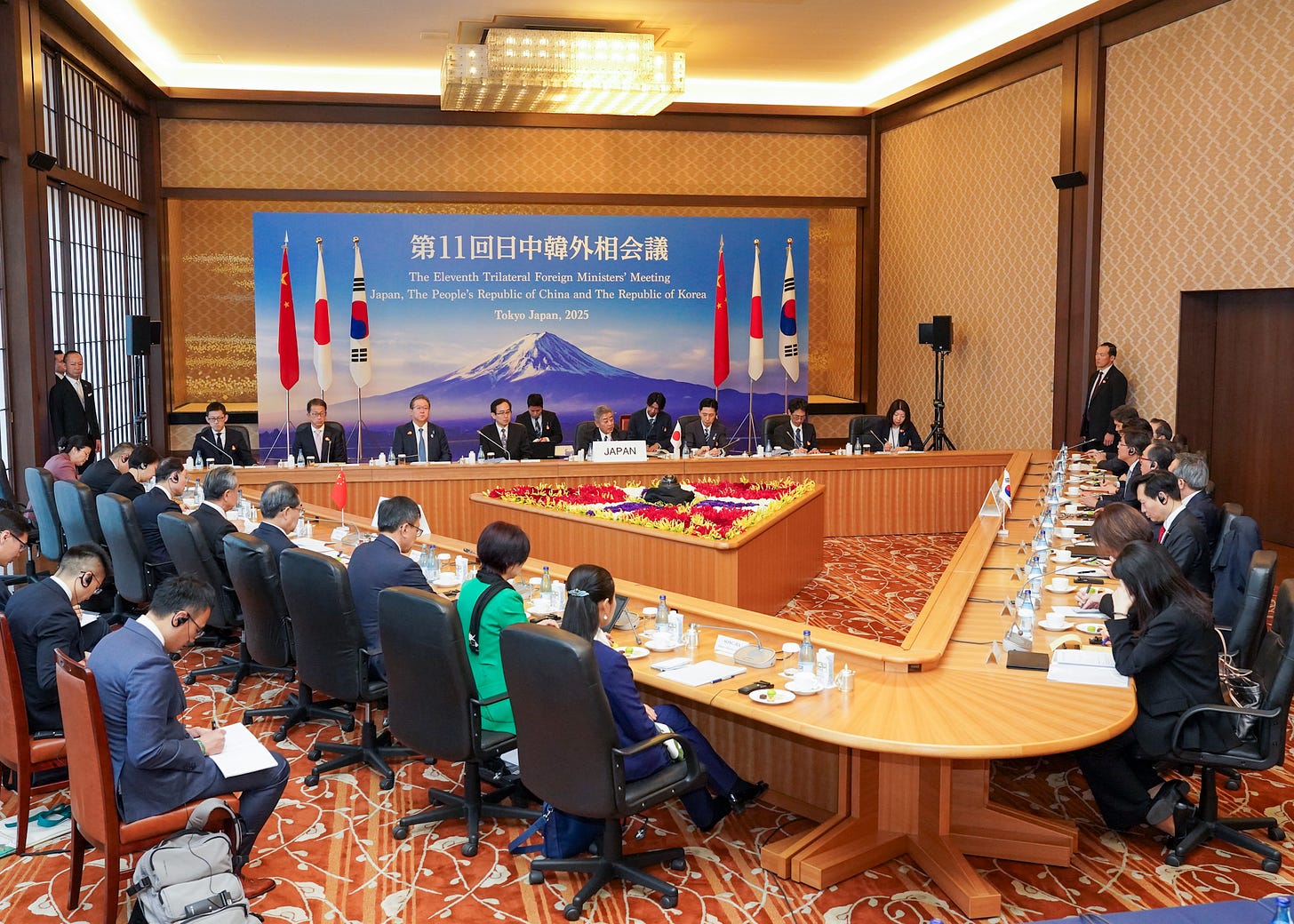

Japan, China, and South Korea’s foreign ministers met in Tokyo, talking up regional cooperation, economic ties, and cultural exchanges. But the real takeaways? Japan’s growing unease over US unpredictability, China’s positioning against Trump’s trade policies, and the usual deadlock over North Korea.

Before the talks, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba called for “future-oriented cooperation,” saying the three nations could make a global contribution by working together. But Japan is unsettled. Trump’s second-term turmoil and treatment of allies are fueling fears of a US retreat from the Indo-Pacific. Japan doesn’t want to be left exposed in a power vacuum, but there’s little political will to do what many believe is necessary. The legal barriers to expanding defense are gone. The money isn’t there.

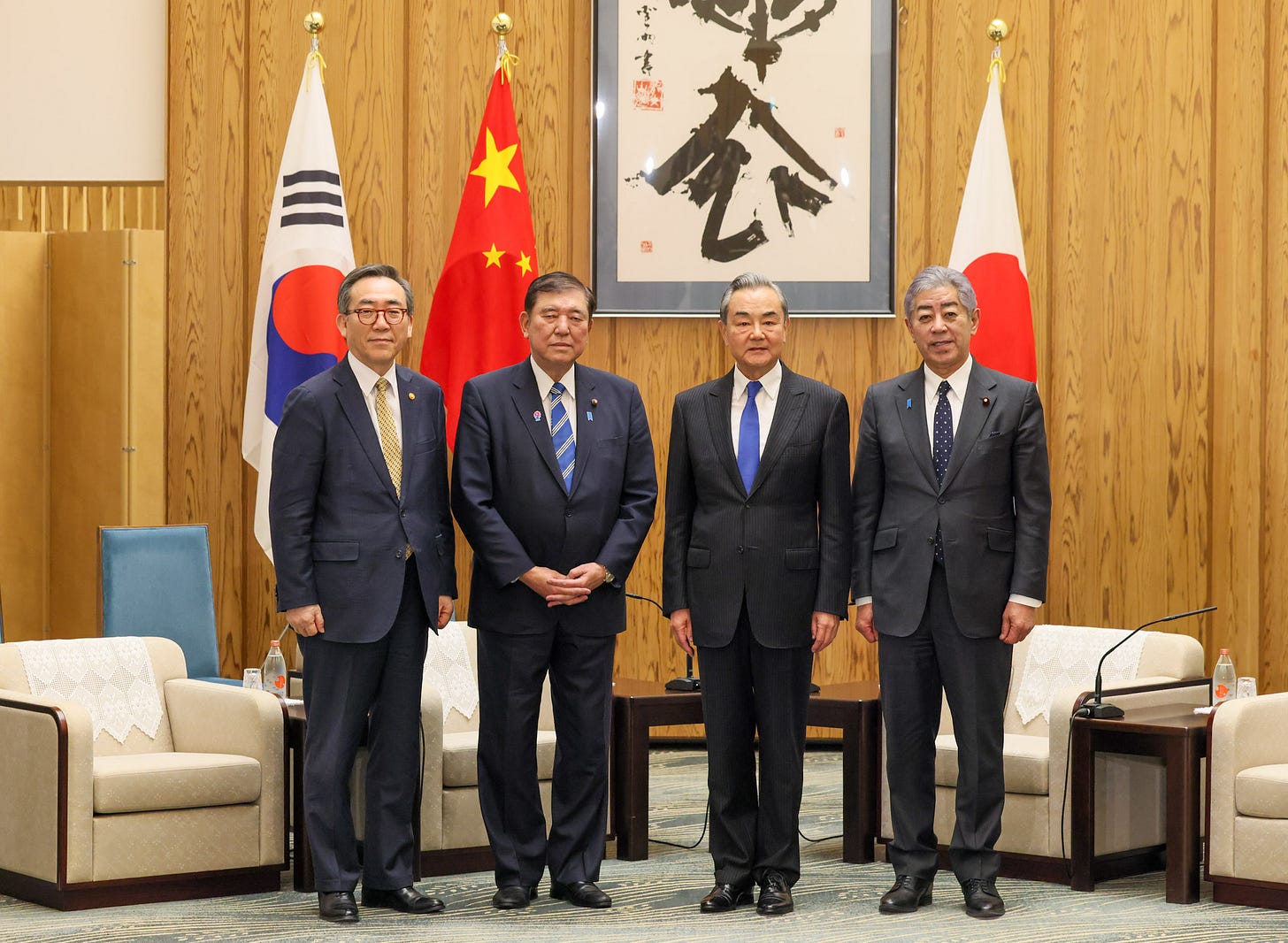

On North Korea, Japanese Foreign Minister Takeshi Iwaya repeated the usual demands on nuclear disarmament and the abducted Japanese citizens. But after decades of failed negotiations, most believe Pyongyang neither has the will nor even the means to return the kidnapped, dead or alive. Iwaya also expressed concern over North Korea’s nuclear and missile development and its growing military ties with Russia. Past talking points repeated. Japan made demands. China called for diplomacy.

China’s Wang Yi kept his message vague, calling for “political solutions” and urging “goodwill from all sides.” At the post-meeting press conference, he stuck to the line that deeper cooperation would benefit all three nations. Wang noted that this year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the war and said, “This is an important year to look back on history, reflect on it, and draw useful lessons from it. The three countries should continue to face history squarely and promote the healthy development of cooperation with a future-oriented spirit.”

But while Beijing talks cooperation, China routinely probes Japanese airspace and waters, prompting regular scrambles by Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. Hardly a foundation for “stability and order.”

South Korean Foreign Minister Cho Tae-Yul, representing a government that JAPAN UNFILTERED sees as having undergone a “self-coup,” offered little beyond stock calls for stability and dialogue. With Seoul still recovering from its own political upheaval, Cho’s role felt mostly ornamental.

The meeting ended with no real breakthroughs. Officially, it was about economic ties, trade, and cultural exchange. Unofficially, Japan is watching the regional balance shift and hedging against the unknown.

After the summit wrapped, Tokyo issued a rare pushback on Beijing’s narrative. China’s foreign ministry claimed Prime Minister Ishiba had expressed “respect” for its position. Japan publicly denied it, lodged a formal protest, and called the statement “factually incorrect.”

According to Tokyo, Ishiba had instead raised unresolved concerns: tensions in the East China Sea, the safety of Japanese nationals in China, the detention of Japanese citizens, and China’s import bans on Japanese seafood and agricultural goods. No such statement of “respect” was made.

It was a rare move. Tokyo doesn’t usually talk back. Past leaders like Shinzo Abe handled Beijing with kid gloves.